If you want, you can analyze multiple network connections at once by pressing “Shift + Left-click.”

#WIRESHARK APP FOR IPHONE CODE#

Where inject.js calls startTLSKeylogger from the code share.Īfter capturing some traffic we can verify that the keys work with tshark as follows.

frida -U \ -f \ -codeshare k0nserv/tls-keylogger \ -l inject.js \ -o out.keylog \ With the above Frida snippet we can dump the TLS session keys the app generates, while running a TCP dump on rvi0 to capture the encrypted traffic. This method relies on us being able to find pointers to the two functions SSL_CTX_new and SSL_CTX_set_keylog_callback in the binary, luckily for me these were both external symbols of a dynamic framework.

I’ve created a Frida Codeshare that does this. Then we can simply call SSL_CTX_set_keylog_callback directly without needing to rely on known offsets, which are brittle. With this knowledge we can hook SSL_CTX_new and get a pointer to every SSL_CTX from its return value. I realised that all SSL_CTX are created via the SSL_CTX_new function and that there’s a dedicated function, SSL_CTX_set_keylog_callback, for setting the keylog callback. Andy’s method relies on knowing a specific offset for the keylog callback function in the SSL_CTX struct and hooking SSL_CTX_set_info_callback to set this value. After some Googling, I found a blog post by Andy Davies which described a method to dump the TLS sessions keys from BoringSSL. The specific app that I was looking at used BoringSSL for TLS. TLS also reveals a tiny bit of information but the majority of the traffic is hidden behind encryption. With DNS queries in the clear we get a few more clues. While we are capturing the traffic, all HTTPS traffic from a custom stack will be encrypted and opaque to us. This will create a virtual network interface typically called rvi0 which we can configure Wireshark to use. Now we can create a virtual interface for the device. It’s available in Xcode under Window > Device and Simulators but can also be found with the ideviceinfo utility from libimobiledevice. To do this we first need to find the UUID of the device.

#WIRESHARK APP FOR IPHONE MAC#

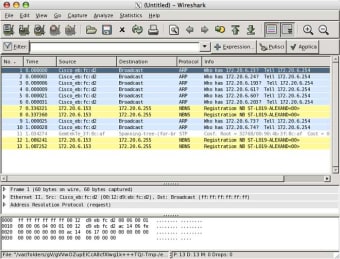

With rvictl we can create a virtual interface on a mac that will capture all packets sent by a mobile device attached via USB. Apple provides a utility called Remote Virtual Interface Tool, rvictl for short, which does just this. To capture traffic on a remote device we need to make it visible to Wireshark. To figure this out I reached for Wireshark to capture all the traffic on the device. Luckily for me, it was obvious from the app’s behaviour that it was doing some form of networking. My modus operandi is to start with mitmproxy or Burp Suite, but in this case doing so meant I missed all of the app’s traffic. If you aren’t attentive you can even miss the traffic altogether as I almost did. Apps that use their own HTTP and TLS stack typically don’t respect system proxies and their traffic is completely invisible to these tools. This can be used with tools like mitmproxy, burp suite, or Charles to intercept or even modify network traffic. Recently, I was investigating an app like this and found myself having to intercept its HTTP traffic.Īpps that rely on system libraries will respect any HTTP(s) proxies configure on the device. This poses a problem for anyone trying to snoop on the apps network traffic. There are many reasons to do this, but the most common one I’ve encountered is apps that use a shared core, typically written in C++, which is used in applications on different platforms. Some iOS apps ship their own HTTP and TLS stack instead of relying on Apple’s NSURLSession or the lower level frameworks it relies on.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)